Fifteen years ago, Sylvia Hatchell and her husband, Sammy, nailed a sign to the big oak tree next to the blueberry patch on their 200-acre property in the mountains of Asheville, N.C. The sign read:

Lineberger Cancer Center Blueberries Patch

Honor System

Mail checks to PO Box 2411

Chapel Hill, NC

Hatchell, the Hall of Fame women’s basketball coach at the University of North Carolina, worked often with Lineberger, a cancer research and treatment center at UNC. Though Hatchell had never had cancer, she knew blueberries were a “super food” of sorts when it came to cancer prevention, so she figured her property of 250 bushes, there in the valley beneath her log cabin, might be a clever way to raise money for Lineberger.

To her surprise, she began receiving check after check for the blueberries to her campus mailbox, which she presented to Lineberger a few months later. When she first presented them the checks, one of the doctors exclaimed, “So you’re the one who is behind the blueberry patch! We keep getting checks for $10 or $15 with ‘blueberries’ written on the check!”

Even crazier, a few years later, there was a board meeting at Lineberger and the guest speaker had first heard about Lineberger—no, not online or on television—but because she had been picking blueberries in Asheville and had seen Hatchell’s sign. One of the Lineberger executives laughed and said, “You know, it’s funny that here we are discussing all these complex marketing strategies and it was because of Coach Hatchell’s blueberry patch that we have our guest speaker today.”

At the time, these were merely comical stories, and perhaps they still are. Twelve years later, however, Hatchell would be at Lineberger for a different reason—and her life would be in their hands.

The summer heading into the 2013-14 basketball season, Sylvia Hatchell had an eerie dream that she was sitting in the stands at Carmichael Arena watching her team play on the court below.

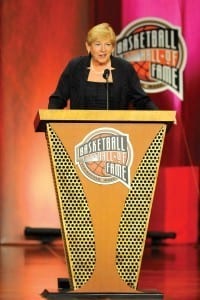

The dream made little sense. Hatchell, after all, was flying high. She had the top-ranked freshman class in the country and would be inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in September, the most prestigious honor in the sport.

That Labor Day, one week before the Naismith induction ceremony, Hatchell went in for her annual physical and found out that her white blood cell count was severely low.

Doctors told her to wear a mask when flying on an airplane and to refrain from shaking hands with people. Hatchell, typically strong-willed, responded, “Look, I’m going to the Naismith; I’m going to be shaking hands with thousands of people this weekend; you don’t understand.” (Hatchell says there are only two things in her life (both ending in “Smith”) that have awed her to the point of shock because of the caliber of basketball greats in attendance—Dean Smith’s funeral and the Naismith.)

“I shook plenty of hands,” Hatchell laughs.

In the weeks that followed Hatchell’s return to Chapel Hill, she sought out second and third and fourth opinions from doctors. With each test, her white blood cell count was low. Doctors believed she might have a viral infection, which seemed minor enough for her to move on and dive into recruiting, as she always did, as she always dove into everything.

Her fatigue and inability to recover, however, led her to schedule a bone-marrow biopsy at Lineberger one Friday morning. That evening, Hatchell was in her Chapel Hill home hanging out with one of her friends when Hatchell’s phone began to ring. She answered.

It was the doctor from Lineberger Cancer Center.

That’s when the doctor delivered the news to Hatchell that she had acute myeloid leukemia, a severe form of blood cancer that is especially fatal for victims over 60 years old (5 percent survive past five years of diagnosis). Hatchell was 61 at the time.

“We have to get you in here,” the doctor said.

“When?” she asked.

“Tomorrow,” the doctor said.

Hatchell was met by disbelief. Not her. Not now. She was as busy as she had ever been, working just as hard as she had ever worked. She was on top of the world, having just been inducted into the Naismith Hall of Fame, about to enter the season with the best recruiting class in the nation, but in an instant—in a single phone call—all that became the furthest thing from her mind.

“I was thinking to myself, ‘I have too many things going on in my life to be told that I have to go to the hospital tomorrow,’” Hatchell says.

On top of that, Hatchell and her closest friends from all over the country had plans to spend the upcoming week at her cabin in Asheville—now those plans were thrown out the window, as well. Hatchell asked her secretary to notify each one of them that she had a health issue.

On Saturday morning, Hatchell met up with her coaching staff and delivered the news. That afternoon, she checked into Lineberger. And that evening in the hospital, one of her friends, an oncologist from Nashville named Jackie Koss, called Hatchell and asked her, “What’s going on?”

“Jackie,” Hatchell said, “I have leukemia.”

“I’m on my way,” Jackie responded.

Throughout the rest of the evening, doctors ran tests in preparation for Hatchell’s chemotherapy on Sunday afternoon.

Everything was happening so quickly.

“That night was really hard for me just because of the reality of what was going on,” Hatchell says. “That was the hardest time of just accepting what was happening. I sent my husband and son home (that night) and that was hard…I cried myself to sleep.”

When Hatchell awoke the next morning, Koss, who had apparently driven through the night, was standing at the foot of her bed.

Oddly, the most difficult thing for Hatchell on Sunday wasn’t beginning the chemotherapy—it was telling her team that she would be sidelined indefinitely.

Oddly, the most difficult thing for Hatchell on Sunday wasn’t beginning the chemotherapy—it was telling her team that she would be sidelined indefinitely.

Later in the day, her players came to Lineberger and they had a team meeting in a conference room at the cancer center. Hatchell had to wear a mask.

“I didn’t know the timeline,” Hatchell says. “Those kids were just devastated.”

Hatchell’s players brought a blue and white rope to the hospital, which they would traditionally hold as a team any time someone was going through a hard time—symbolizing that they would hold the rope for one another throughout the duration of the trial. In this case, her players would hold the rope for their coach.

This would be the most trying struggle of Hatchell’s life, no longer able to do what she loved the most: coach.

Throughout Hatchell’s cancer treatment, the doctors would sometimes let her sit up in the corner of Carmichael Arena and watch practice if Hatchell’s white blood cell numbers were not too low. They even allowed her to attend a couple of games. (The season marked her first time not coaching since January 1989, when she missed two games due to the birth of her son, Van.)

“I kept thinking back about that dream: Why would I be sitting in the stands watching my team play?” Hatchell says. “But here I was, just a few months later. I’d be up there and if it was close at the end of the game, I would have to leave. I couldn’t take it. I wanted control. I wanted to help them. I wanted to be out there coaching and help them pull the game out. But I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t go to the locker room. I couldn’t do anything. It was killing me, the fact that they were battling so hard, and I was supposed to be out there with them, coaching them, but I couldn’t do anything.”

It was a mystery to Hatchell that she had leukemia in the first place. Many times, leukemia is hereditary, but no one in Hatchell’s family had leukemia; sometimes it’s caused by smoking, but Hatchell hadn’t smoked a day of her life; other times it’s caused by working with pesticides, but Hatchell had never worked much with pesticides. The only thing she could come up with, as she reflected on her life, was that it was caused by the environment when she and her friend Kay Yow, the legendary coach who died of breast cancer in 2009, coached the Goodwill Games and World Championships in 1986 in Russia. There, she had spent time in Moscow, which was close to Chernobyl, the site of the worst nuclear power plant accident in history, which had occurred that year. Sometimes it takes 20 years for environmental effects to be revealed. It had been 26.

The remainder of the year, Hatchell went through four cycles of chemotherapy—knocking her immune system completely flat, flushing out the cancer cells, and eradicating her white blood cells and neutrophils to the point that she wouldn’t have the strength to fight a single germ.

“There were nights I went to bed just praying I would wake up the next morning because I was so weak,” Hatchell says. “I was so physically weak.”

But Hatchell says there were three things that carried her through: her attitude, exercise and support system.

For example, when her hair began to fall out, she called her hair stylist, Wanda, and said, “Can you come over tomorrow afternoon? Bring your shears: We are going to have a ‘Shave Coach Hatchell’s Head Party.’” Hatchell invited the doctors and nurses, and that’s exactly what she did—she took something that most might find sobering or shocking and turned it into a party.

First, she had one side of her head shaved, then styled her remaining hair by pulling it over to the same side. (“I looked like a punk rocker,” Hatchell laughs.) Next, came the Mohawk; then the rat-tail; then a completely shaved head with “GO HEELS!” painted in the back.

From the very start, Hatchell set the stage for her looming battle with cancer by dedicating herself to a positive mentality.

“She refused to wear a hospital gown,” says Hatchell’s husband, Sammy. “She exercised after every chemo session. She was fiercely determined.”

She says her Christian faith helped her remain positive, as well.

“I was in there for a month (at the beginning), and that was hard,” Hatchell says. “Cabin fever for a person like me who is used to traveling and has every second of my day full of things—that was tough. But it gives you time to reflect and think about your life and who you are and just about your relationship with God, and the fact that He was going to take care of me, and I really felt His arms around me at times…You don’t know the outcome all the time, but you know you are going to be okay…There are times you can just feel the Holy Spirit. It’s like a wind. You can’t see it, but you know it’s there.”

The other thing that fed into her positive attitude was her dedication to exercise. She had entered the hospital in, quite possibly, the best shape of her life, and she was committed to staying active, no matter how weak she physically became. Her exercise oncologist, Claudio Battaglini, would lead her through workouts with free weights and resistance bands, there in her hospital room, and Hatchell says that each day she would attempt to walk 17 laps around the fourth floor of the cancer hospital—even if she had to use her IV stand as a crutch. Ultimately, she believes doing these things not only strengthened her physically but also affected her mentally because she was not caving to her weakness.

The other thing that fed into her positive attitude was her dedication to exercise. She had entered the hospital in, quite possibly, the best shape of her life, and she was committed to staying active, no matter how weak she physically became. Her exercise oncologist, Claudio Battaglini, would lead her through workouts with free weights and resistance bands, there in her hospital room, and Hatchell says that each day she would attempt to walk 17 laps around the fourth floor of the cancer hospital—even if she had to use her IV stand as a crutch. Ultimately, she believes doing these things not only strengthened her physically but also affected her mentally because she was not caving to her weakness.

“The word to describe Coach Hatchell is ‘indefatigable,’” says Dr. Shelley Earp, director of UNC Cancer Care. “Her response to diagnosis of leukemia was similar to her response to life and coaching. She was going to win this battle. She kept a positive outlook and exercised with her trainer daily no matter how badly she felt. She was going to do everything in her power to defeat her disease.”

Lastly, she says her support system, her family and friends, helped her keep her spirits high. Her closest girl friends, for example—who she had planned to vacation with at her cabin—arranged a schedule, from Oct. 11 to Apr. 17, to constantly visit and take care of Hatchell, whether she was at the hospital or at home. One would not leave until the other arrived. “I did not spend one second by myself,” Hatchell says.

Says her friend Jackie Koss: “My main purpose was just to be the friend of 40 years that Sylvia has always been to me.”

Hatchell says that the fraternity of coaches, and even media members, were also constantly encouraging her—whether it was UNC head coach Roy Williams or Duke head coach Mike Krzyzewski or ACC commissioner John Swofford or former North Carolina governor Beverly Perdue or legendary coach Pat Summit or Good Morning America’s Robin Roberts. “I heard from just about everyone except for President Obama,” Hatchell laughs.

Another one of the people who encouraged her was the late Stuart Scott.

“He would call me and text me,” Hatchell says. “It was his third bout with cancer, and he would say, ‘Girl, today, you are going to feel like crap, but you can do it; you have to keep fighting, girl; I’m here for you. If you need me, you call me, you text me.’ I got a text from him in December of last year, and that was right before he passed away a couple months later.”

Ann Graham, the daughter of evangelist Billy Graham, once told her dear friend, Sylvia Hatchell, at the start of her bout with cancer, that “Jesus sang praises to God before He went to the cross, even though he knew what he was about to do.”

Ann Graham, the daughter of evangelist Billy Graham, once told her dear friend, Sylvia Hatchell, at the start of her bout with cancer, that “Jesus sang praises to God before He went to the cross, even though he knew what he was about to do.”

This idea—that Jesus could adapt a lifestyle of praise and gratitude despite his coming suffering—remained with Hatchell throughout her fight. Perhaps she, too, could still sing praises.

“You know,” Hatchell says, “a long time ago, I said, ‘I’m all Yours; use me how You want to use me.’ Now, when you say that, you better mean it, because you don’t know what He may have planned. I said that many years ago, and I’ve always tried to do that. But, like I said, I had my life planned out…I was planning on winning another national championship…But He had a different plan. In the long run, His plan is going to be better, but it’s hard.”

One evening in the middle of her fight with leukemia, she was listening to a sermon by evangelist David Jeremiah, whose sister Mary Alice had been a successful women’s basketball coach. Hatchell wrote these words on a piece of paper: “A godly woman in the center of God’s will is immortal until God is done with her.” Each morning, she would begin her day by reading these words. What a strange thing it was for her to believe that—even in her bout with leukemia, in the pits of her suffering—she was at the center of God’s will!

“Every day when I open my eyes, I say, ‘God, put the opportunities in front of me, and I promise You I will take advantage of them. Just put them in front of me.’”

This redemptive outlook on her sufferings inspired her to look outward, not inward, and use her story to impact as many people as she possibly could. For example, at one point, doctors thought she might need to find a bone marrow match, so Hatchell, with her platform, began hosting Be The Match campaigns at Carmichael Arena. After she spoke to the crowd at halftime of a game against Maryland, she remembers the arena to be virtually empty in the second half—that’s because fans were out in the atrium getting their cheeks swabbed for Be The Match.

This redemptive outlook on her sufferings inspired her to look outward, not inward, and use her story to impact as many people as she possibly could. For example, at one point, doctors thought she might need to find a bone marrow match, so Hatchell, with her platform, began hosting Be The Match campaigns at Carmichael Arena. After she spoke to the crowd at halftime of a game against Maryland, she remembers the arena to be virtually empty in the second half—that’s because fans were out in the atrium getting their cheeks swabbed for Be The Match.

Other schools began hosting Be The Match campaigns, as well, inspired by Hatchell. For example, the women’s basketball team at Wingate University, just east of Charlotte, N.C., hosted a campaign, and one of its players, Jasmine DeBerry, ended up being a match for a 9-year-old girl in New York (DeBerry had been in the registry since her freshman year). Since 2014, Hatchell already knows of three lives that have been saved from one of these campaigns.

Says a teary-eyed Hatchell: “I told my husband, ‘Sammy, as hard as the treatments were and as weak as I was, with all I had to go through, if me having leukemia saved someone’s life, then it was worth it.’ You never know why things happen, but there is a reason…people’s lives have been affected and saved because of what I’ve been through.”

On a quiet August afternoon, Hatchell, on the brink of entering her second full season with the Tar Heels since her cancer went into remission in January 2014, is being interviewed on the floor of Carmichael Arena.

On a quiet August afternoon, Hatchell, on the brink of entering her second full season with the Tar Heels since her cancer went into remission in January 2014, is being interviewed on the floor of Carmichael Arena.

Could there be more of a perfect place for her to share her story than here in Carmichael, this place she calls “Blue Heaven”? (“In my book, there’s only one heaven better than this,” she says.)

She has coached in this place for nearly three decades, here at the University of North Carolina, where she has given her life’s work. It’s where she has led practice, day after day. It’s where games were won and where games were lost. Behind her, up in the balcony, is where she watched games while stricken with leukemia, forced to wear a mask and unable to coach. Up to her right is where she would sit and watch practice. On this very floor is where she spoke to a crowd at halftime, asking them to join the Be The Match campaign. And the stands surrounding her on this day are just as empty now as they were after her halftime speech. Games were not only won in this place, but lives were also saved.

And, though she has held the same title at UNC since 1986, this is a different Sylvia Hatchell than the one at this time of year in 2013, just weeks before she was inducted into the Naismith. Now, Hatchell says she is 95 percent healthy. She says she is just as passionate about coaching, if not more so, and just as competitive, if not more so. (“I’ve never been a good loser, and I hope I never become one,” she laughs.) But the real difference in Hatchell is her perspective on life.

“I have no fears on this world or thereafter,” Hatchell says. “You go through what I’ve been through and get as close to death…again, I have no fears. I know who wins. I know what the final outcome is…I feel like I’ve gone from being a Christian to being a disciple.”

Perhaps there is no calling that is quite like that of a disciple—immortal, at the center of God’s will, whether in joy or in suffering.

Says Hatchell: “With what I’ve been through, I say, ‘Each and every day, I let no one and nothing take my joy away.’”

Over the last two years, Hatchell has proved that no one and nothing can.

By Stephen Copeland

Stephen Copeland is a staff writer and columnist at Sports Spectrum magazine. This story was published in Sports Spectrum’s Fall 2015 DigiMag. Log in HERE to view the issue. Subscribe HERE to receive eight issues of Sports Spectrum a year.