The drive from Lake Tahoe to Seattle is about 13 hours.

The road, like a river, winds its way through an array of landscapes—mountains, valleys, forests, desert, and high plains—as if God is showcasing His most beautiful paintings.

Nick Visconti is on the road, the river. He doesn’t second-guess his direction, just as water doesn’t question its current.

There’s something as mysterious, unexplainable, and true as gravity that’s pushing him. Like the flow of a river, he can feel its direction. He cannot see it. But he can feel it—the thrill of adventure as he looks ahead, hand on the wheel, toward an open road of endless opportunity, yet a reality as poignant as lost love, as he sees everything in his rear-view mirror vanish quickly behind him.

His comfort zone and contentment.

His family and friends.

Everything he once knew.

Lost in the miles.

Visconti is wearing a snowcap, aviators, flannel, and tight Sessions jeans, the same pants he snowboards in. He has his windows down and is blasting 90’s grunge rock. He looks hip, like he could play guitar in coffee shops, but also hard-core, like a Johnny-Knoxville-sort-of-crazy, like he snowboards down mountains and leaps off cliffs…which, he does.

If you saw him on the street, you may think he painted graffiti on a library, but if you heard him speak, you may think he’s read every book in the library. He’s extreme like a skydiver and reckless like a cowboy, but he has the vernacular of a poet and the gentleness of a counselor.

When ESPN asked him about his past “record” in snowboarding competitions, he replied, “I don’t keep records because I don’t spin vinyl.” When they asked if there was anything else he’d like to talk about, he said, “This morning I danced with the sunrise to the Moulin Rouge soundtrack.” Visconti, the 2012 Winter X Games bronze medalist in the snowboarding street contest, is his own man.

“The drive to Seattle was vivid imagery, almost foreshadowing what I was about to experience—really, what we will experience in all of life because of the different landscapes and terrains,” Visconti says softly and elegantly, almost as if he’s reading. “There were different weather patterns. There was blue sky, where all you could see was the expansion of the sky meeting the horizon in dark, vivid, blue and beautiful colors. At the same time, I would go over areas of the northwest, and it was dreary, doom, gloom and torrential downpours. Everything metaphorically spoke to not only how I was feeling but foreshadowed life as a whole…You can clop all those words together and create a picture. But at the end of the day, I was feeling.”

Leaving northern California for Seattle made about as much sense as the 6-foot, 155-pound Visconti dropping snowboarding to be a linebacker. It was where he had spent his entire life, where his family lived, where his closest friends lived, where the girl he loved lived. It was where his snowboarding career began and where it blossomed. Northern California claimed him as its own. It was where he was loved.

Visconti’s life, on the outside, had never looked better. After eight years of balancing snowboarding and his college education, taking one semester of school each year, he had finally attained his bachelor’s degree in Speech Communications from the University of Nevada. One of his lifelong academic goals, after nearly a decade of dedication, was finally complete.

But it didn’t stop there.

After receiving his degree that December, Visconti took bronze in the street contest of the 2012 Winter X Games in January, thus earning him an automatic invite to the 2013 Winter X Games on Jan. 24-27. In a year, he had gone from aspiring snowboarder and student to bronze medalist and graduate. He had achieved two of the most important things he sought after in life: academic and athletic success.

“Those were very grand things,” Visconti says. “Although I want them to continue evolving, when I kind of came to climactic endpoints of both of those accomplishments, I was kind of questioning, ‘Well, what’s next?’ It was somewhat mediocre and felt somewhat empty…Aesthetically, things looked great. Internally, I felt a lack of direction. I felt hollowness, but more than anything, an insurmountable desire to make a change. Seattle was that change.”

In April, Visconti left everything he knew. He wanted more than academic and athletic accolades. He craved meaning.

Why Seattle, he doesn’t exactly know. He just says it was a “faith-based” move. And that’s the thing about a river’s water; it doesn’t have to explain its direction. It simply flows. There’s something pushing it.

“That life was something that, at that point, was lackluster,” he says of northern California. “It was dim-lit, and I was ready to shine.”

≈≈≈

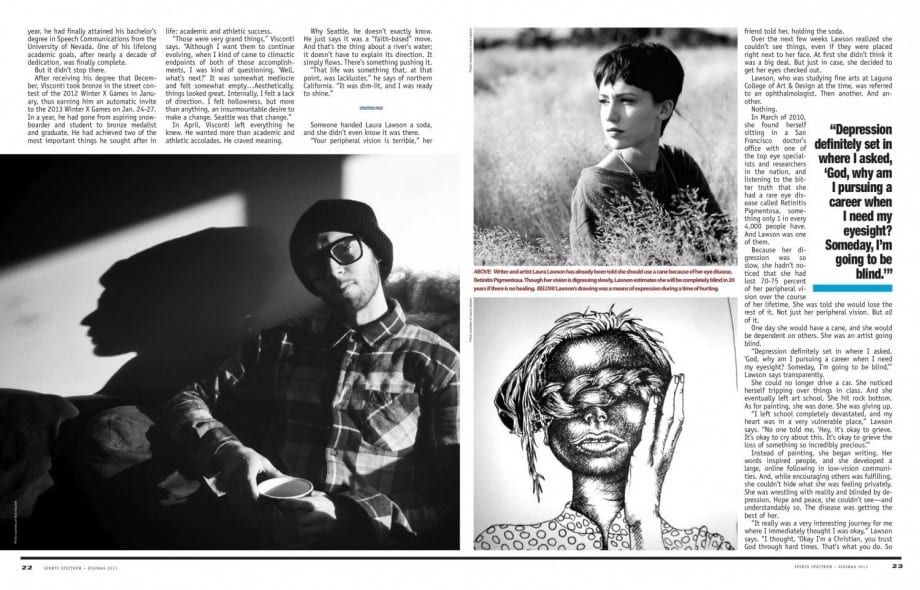

Someone handed Laura Lawson a soda, and she didn’t even know it was there.

“Your peripheral vision is terrible,” her friend told her, holding the soda.

Over the next few weeks Lawson realized she couldn’t see things, even if they were placed right next to her face. At first she didn’t think it was a big deal. But just in case, she decided to get her eyes checked out.

Lawson, who was studying fine arts at Laguna College of Art & Design at the time, was referred to an ophthalmologist. Then another. And another.

Nothing.

In March of 2010, she found herself sitting in a San Francisco doctor’s office with one of the top eye specialists and researchers in the nation, and listening to the bitter truth that she had a rare eye disease called Retinitis Pigmentosa, something only 1 in every 4,000 people have. And Lawson was one of them.

Because her digression was so slow, she hadn’t noticed that she had lost 70-75 percent of her peripheral vision over the course of her lifetime. She was told she would lose the rest of it. Not just her peripheral vision. But all of it.

One day she would have a cane, and she would be dependent on others. She was an artist going blind.

“Depression definitely set in where I asked, ‘God, why am I pursuing a career when I need my eyesight? Someday, I’m going to be blind,’” Lawson says transparently.

She could no longer drive a car. She noticed herself tripping over things in class. And she eventually left art school. She hit rock bottom. As for painting, she was done. She was giving up.

“I left school completely devastated, and my heart was in a very vulnerable place,” Lawson says. “No one told me, ‘Hey, it’s okay to grieve. It’s okay to cry about this. It’s okay to grieve the loss of something so incredibly precious.’”

Instead of painting, she began writing. Her words inspired people, and she developed a large, online following in low-vision communities. And, while encouraging others was fulfilling, she couldn’t hide what she was feeling privately. She was wrestling with reality and blinded by depression. Hope and peace, she couldn’t see—and understandably so. The disease was getting the best of her.

“It really was a very interesting journey for me where I immediately thought I was okay,” Lawson says. “I thought, ‘Okay I’m a Christian, you trust God through hard times. That’s what you do. So I’m fine.’ But all the while, I was actually really suffering. I was really hurting. There was this huge pressure I put on myself to be okay and trust God. I felt like, as a good Christian, I shouldn’t be questioning this. I shouldn’t be questioning, ‘Why me?’ and I shouldn’t be feeling so sad. I should be able to trust God.

“However, the thing is, I felt like God was grieving right along with me.”

≈≈≈

Nick Visconti got a call one day from Laura Lawson, the girl he had wanted and pursued ever since they met three years before in a northern California wine bar through a mutual friend.

“I’m going to Seattle,” she told him over the phone, the first time he had heard her voice in two months.

“Well, very interesting thing you say that,” he said. “I’m moving to Seattle next week.”

Visconti and Lawson have an interesting past, something Visconti calls a “romantic entanglement.” For three years, Visconti wanted to date her, but their paths never aligned. Visconti was traveling continually, immersed in his snowboarding career and earning a degree. She had art school and was wrestling internally with her disease. He lived in Lake Tahoe. She lived three hours away in the Bay Area.

“Whenever he was in town, we would hang out,” Lawson says. “We always had this spark, but my heart was not in it. I saw someone who had his life on a very exposed platform. Nick is an amazing person, but he is a very intense person and I felt like I wasn’t ready for that kind of relationship.”

Everything changed in Seattle. The two of them began dating and Lawson decided she had finally found her match, that his extremity was exactly what she needed.

“In Seattle, I told him that this is the reality of what I have,” Lawson says. “But the thing with Nick is that he is just adventurous and a daredevil and does not let anything get in his way, and he pursues life to the fullest more than anyone else I’ve ever known, so for God to put him in my life, for me, is like a necessity.

“When Nick and I met (three years ago), I was living very cautiously and letting my disease get the best of me. It’s been largely through dating him that I’ve realized that I need to not let this define me and go out and live life and be adventurous and make the most of my time now…There are times when it gets the best of me, and there are still hard days. It’s an emotional thing. It’s difficult. But he’s just a great example to me of someone who takes risks. What he does for a living is certainly risky in itself, and he really does pull me in a good direction and I think the people who have known me for a long time see that influence.”

Not only did their relationship click in Seattle, but so did their personal lives. Visconti, who is unofficially the first snowboarder to land a “Christ Air” and is “one of the most progressive snowboarders riding today” according to ESPN’s Matt Vanatta, saw his snowboarding platform and ministry grow exponentially. Nations Foundation, a snowboarding ministry that creates stories through film to reach out to the action games culture, contacted Visconti to do a 45-minute year-in-the-life production about him titled “Anthropology,” a project that led to his involvement with World Vision and a snowboarding/mission trip to Africa.

As for Lawson, she started painting again and signed a book deal with Slim Books for her upcoming memoir “Believing is Seeing,” which is about her return to art and her move to Seattle, a project she completed this January.

“When you start trusting God in the small things—He does fulfill his promises and is true to his Word—it’s easier to trust Him in the big things,” Visconti says. “You see that He is not only authoring but perfecting your life according to His will as Scripture promises.

“Once you start to realize that all of this is God’s story, and we’re merely characters in that, being guided by the Holy Spirit, you can let go and give God control and see that He is doing something crazier and more beautiful than you can ever imagine or even write yourself.”

Two days before Christmas, eight months after Lawson and Visconti separately moved to Seattle and began dating, the two of them stood outside on the snow-covered ground at an alpine lake in northern California. Snow slowly fell from the sky, and the sun was shining brightly. It was so still they could hear one another breathe. Visconti got down on one knee, and everything felt right.

≈≈≈

They say seeing is believing, but it’s kind of a lie.

It’s true if taken literally, but false in what it fundamentally implies. It places all belief on what’s known, what you can see. It places no belief in what’s unknown, what takes faith.

You can live your life by the idiom, like much of society, but don’t be surprised when your life lacks risk and adventure, faith and beauty. Don’t be surprised when, like Thomas, your cynicism and doubt betray you, as your hands touch the wounds of Jesus and the Savior responds, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

It’s impossible to flow with the current if all you do is question its direction; to drive to Seattle if all you desire is comfort; to start painting if you’re blinded by the future; to take a risk without belief. The most beautiful things, often times, are the things you can’t see.

“The faith-based life, living according to God’s will, is a mighty and extreme calling, but it’s also a radical calling,” Visconti says, talking gently and quietly. “I still have uncertainties. There’s not a day that goes by that I’m not thankful for what God has done, that I don’t see how He has orchestrated beautifully my life, but there are still things I just don’t understand, a future I’m uncertain of. There’s still the daily grind that has its difficulties and struggles, but,” he says, making a long pause and speaking even quieter, “I do know that I am confident in the fact that He’s got me. That’s what the faith-based life is, not that everything is easy, but that you have hope.”

By Stephen Copeland

Stephen Copeland is a staff writer at Sports Spectrum magazine.